Previously I had to give a wag of the finger to Newsweek, for failure to even mention Robert Culp or put a dinky lil’ picture of him in their multi-page spread of notable folks who passed away in 2010.

This time I give a tip of the hat to New York Times Magazine in their year-end selection of notable folks who passed in 2010 with this interesting reflection on Culp titled “The Self Conscious Hunk.”

Self-conscious? I take it the writer never saw that issue of Oui magazine or the Playboy spread… Ahem…

Anyway, the piece speaks positively of Culp but I have some comments on a couple of points made.

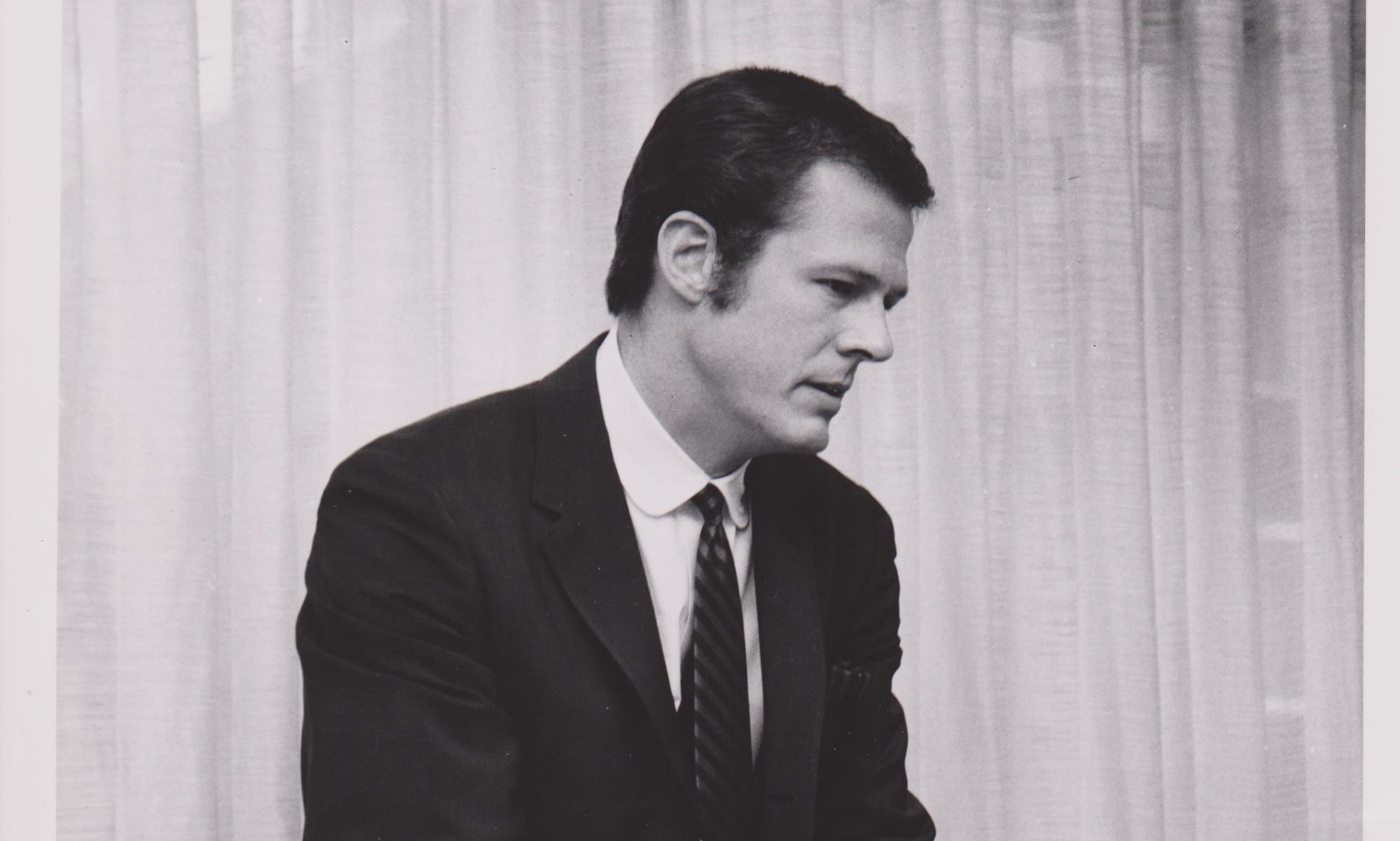

The piece talks about Culp’s “slickness” in reference to his portrayal of Kelly Robinson and what it all meant to be a man in the mid-1960s with the smarm and charm and getting the girls. The first season of I Spy, Kelly’s wardrobe consisted of the expected playboy type clothes, nice suits, ect. His hair was short, jet black and never out of place. He sported ascot ties occasionally, very debonair, along with a Rolex watch and black onyx ring. If your dictionary needed a photo for the word “suave” Robert Culp as Kelly Robinson was it.

The writer went on to say that by the time of 1969’s “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice” Culp’s “slickness” had gotten old and more grizzled actors like Elliot Gould and Jack Nicholson would go on to dominate and represent the whole masculine definition through the 1970s.

Thing was, Culp wasn’t even really that “slick” by 1969. In my own personal observation, by the second season of I Spy, Kelly Robinson was starting to look a little rough around the edges. The hair got a little longer, the grey was threatening to show and Kelly just wasn’t as polished looking as when first introduced. Not that Culp wasn’t still fluid and suave as Robinson, he was. But Culp – through Kelly – looked to be reflecting both the wear and tear of the spy business and Kelly’s own inner demons along with the fast changing times that became the post-1965 world. The revolution, as it was, culturally and socially and the redefining of the role of a man. Ascot ties and close crop hair need not apply.

The writer goes on to say that Culp’s stardom essentially ended after B&C&T&A and that he was “confined largely to supporting roles on TV.” I’m not so sure Culp was “confined.” To say that Culp couldn’t have been of the same super star status as Jack Nicholson is pure crock. Maybe Culp made some decisions in his career that kept it from the super star path, but Culp was no less suited to being on par with any of the other actors who were considered to represent the masculine definition of the 1970s. That Culp couldn’t have been “grizzled” and “emotionally messy?” Sure he could have. With aplomb.

Although I disagree on a couple of points in the piece, I’m not complaining. All matters of opinion are subjective anyway and every one of us sees things a little differently. Still, I tip my hat to the New York Times Magazine for including Culp in their list, not so much to mark his death but, as they explain in their overview of the section, to include him as part of “a collection of narratives that celebrate lives.”

Too bad Newsweek couldn’t spill any ink for him for that.