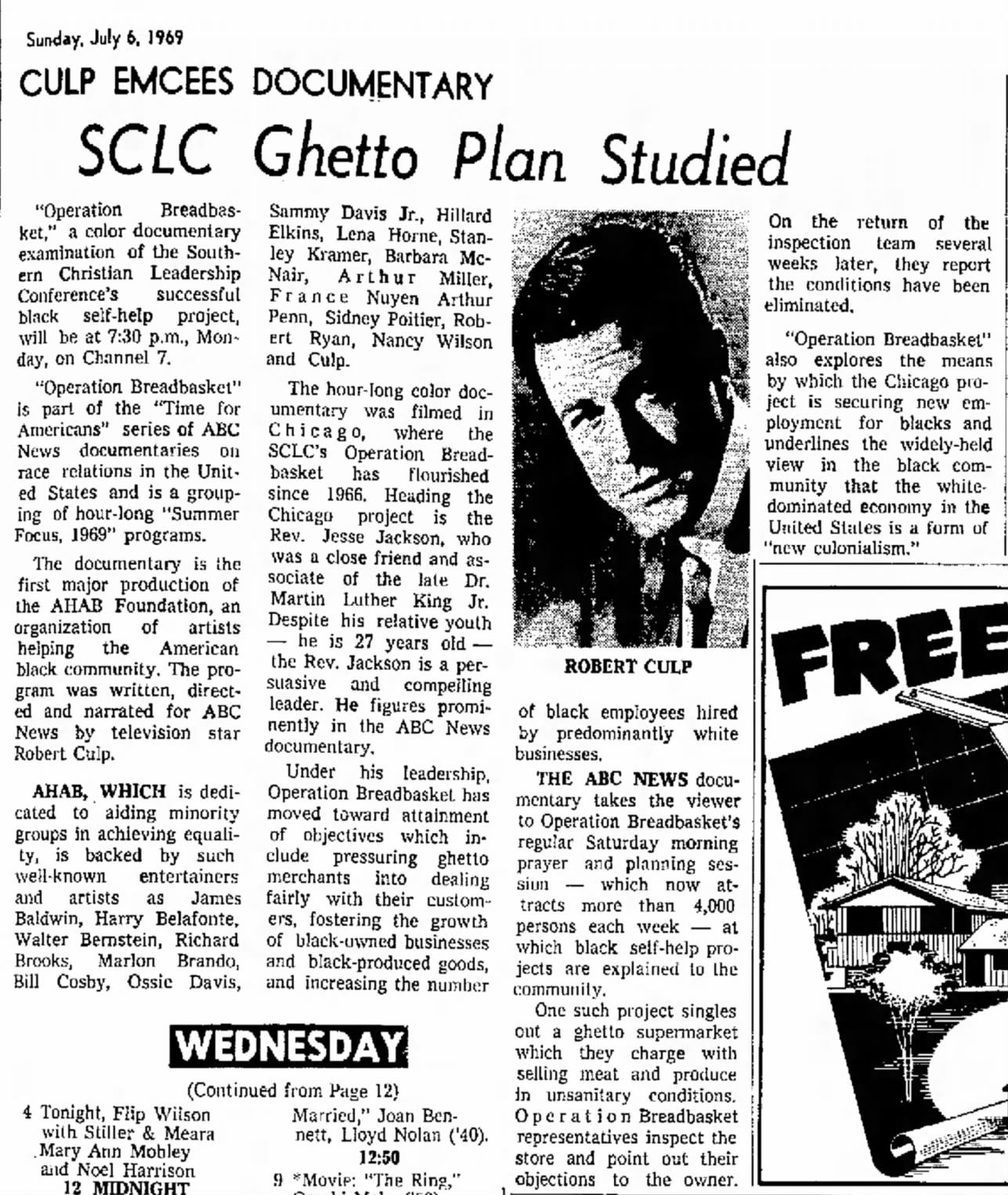

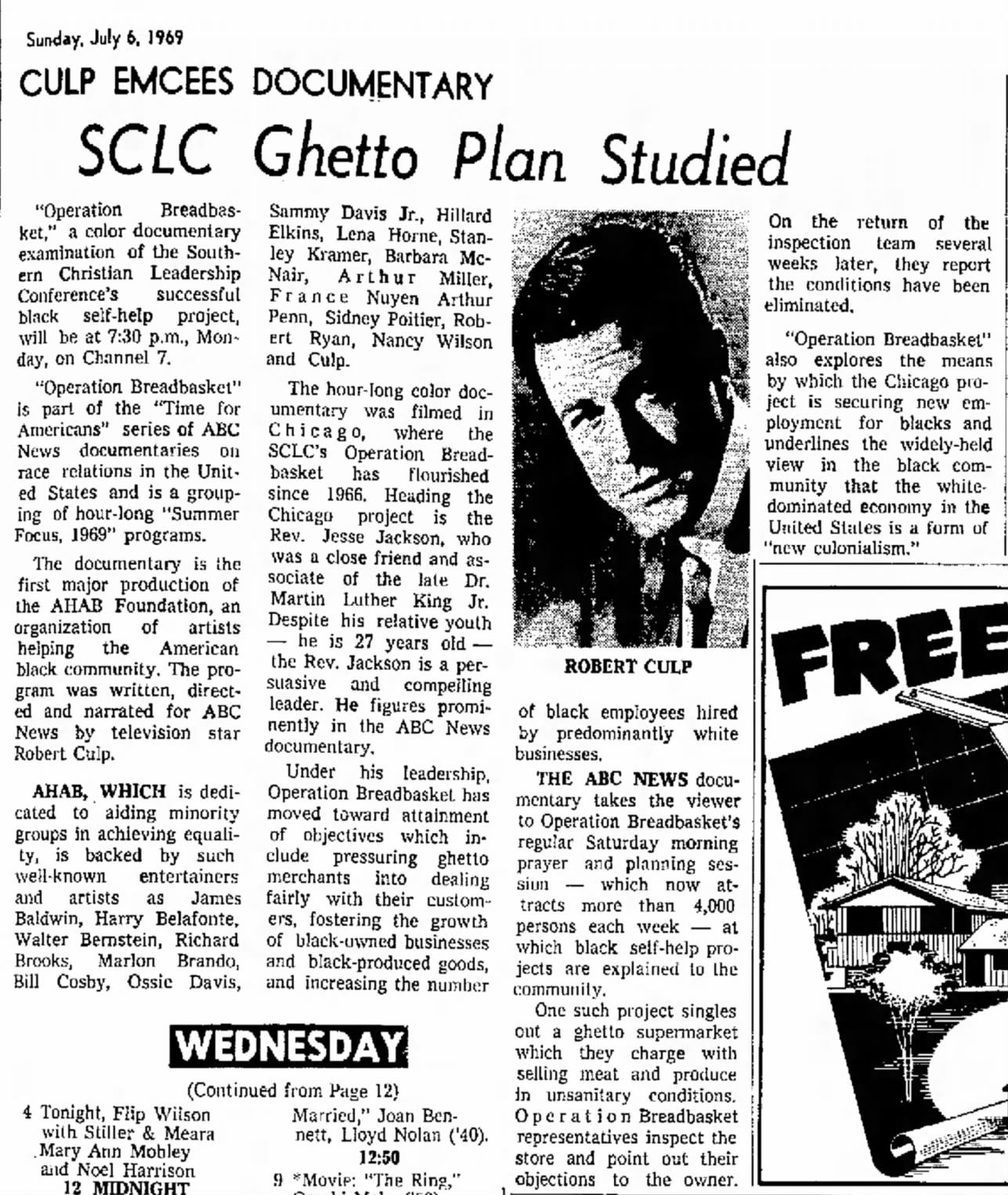

No writer credited, this article appeared in a California newspaper on July 6, 1969.

Sharing the wonderfulness of Robert Culp

No writer credited, this article appeared in a California newspaper on July 6, 1969.

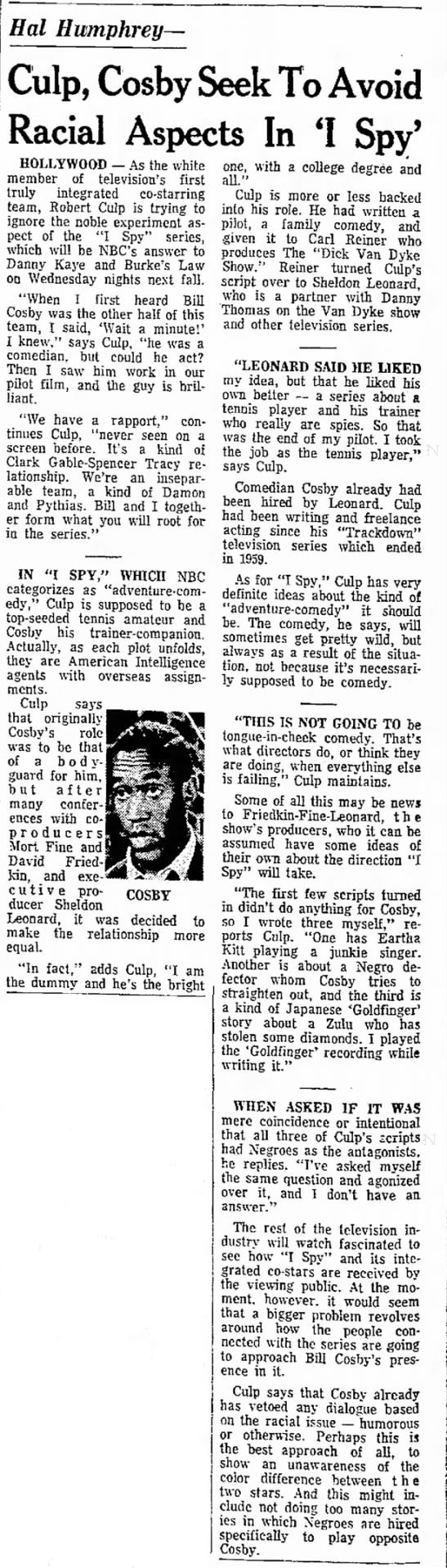

Hal Humphrey’s column from May 17, 1965.

From Motion Picture Magazine, January 1967

By: Bill Cosby (as told to James Gregory)

On I Spy Bob Culp and I are a team. And that’s why I don’t feel anyone should split us up and give an award to just one guy – the way they gave an Emmy just to me a while back. With other comedy teams there is always only one guy who is funny – Jerry Lewis, Lou Costello – but Bob can be as funny as he wants. The two of us make it together. One plays off the other. We do comedy, but there’s no straight man.

On the Emmy Awards show I thanked Bob for helping me learn to act – thereby losing his own chance to win an Emmy for best actor in a dramatic series, for which we had both been nominated. What he had done for me was the finest thing one friend could do for another. He had taken a comedian who knew nothing about acting, and without being selfish he helped me along – eased my tension, gave me pointers, made sure certain things were right. He told me what acting really meant – “This all has to do with what’s inside of you. If you believe what you’re saying your face will show it.”

He taught me about lighting, where to stand, how to move, how to speak up. He wouldn’t let a director make me do something I couldn’t handle yet. He protected me that first year. And he still does at times, if I don’t know what’s going on. I think that’s why he lost the Emmy. He always helped me, and he might just not have had enough time to do certain things for himself.

Of course, he did it to help the whole show too – because Bob knows as well as I do that the strength of the series happens to be the relationship between the two men. If one man goes bad, it all starts to fail. As Bob said a few months ago in an article in MOTION PICTURE,” “The gold in the show is the relationship between Bill and me; and that’s what makes the show.”

Our relationship is important in our personal lives, too. We are very, very close.

Bob came up to me on the set of I Spy and gave me some old Captain Marvel comic books, which he knows I dig, and old Captain America second issue and a Captain Marvel poster. And he wrote me a little note that said, “Thanks a lot for everything.” He thanked me. We sat down and we kind of discussed the awards. And that’s when I told me him that they shouldn’t try to split up a team like us. He saw what I meant, and agreed with me, I told him it really got to me that there was a trophy for only one guy, when that’s not really the way it is – at least not with us.

But I really didn’t have to explain to Bob how I felt. We’re so close that we instinctively understand each other. We even have a certain way that we speak to each other. I don’t know if you’ve ever had a friend who was so close to you that maybe just one word could key you off into – not necessarily fits of laughter, but enjoyable moments, when you’ve both been depressed or tired. For me that particular pick-me-up happens to be Bob Culp.

But I really didn’t have to explain to Bob how I felt. We’re so close that we instinctively understand each other. We even have a certain way that we speak to each other. I don’t know if you’ve ever had a friend who was so close to you that maybe just one word could key you off into – not necessarily fits of laughter, but enjoyable moments, when you’ve both been depressed or tired. For me that particular pick-me-up happens to be Bob Culp.

I don’t think we like the same things as much as we can sit down and really communicate with each other. I can talk with him for a long time and never get bored. We’ve discussed many things, from acting to pro football to lizards – to the beauty of putting an A-bomb together for fun. Or we may talk about some choice, beautiful thing we saw on TV: good acting, good actors, good actresses, good movies. Nothing really deep. We talk occasionally about politics, but neither of us is very active in that field. I wouldn’t back any politician, because I don’t believe in them. I have very little faith in politicians. They will make noises at election time, putting down their opponents, saying, “Hey, you stink … you’re bad!” So forth and so on. Then you put the guy in office, and soon the other guy says, “Look at him! He’s messing up, too.”

I don’t think it’s surprising that Bob and I can discuss so many things so easily, or that we’ve developed our own way of communicating. When you live with somebody 12 hours a day for 5 days out of the week, you get to know him awfully well. And then, in our case, we also go to places around the world together for our show … Hong Kong, Mexico, Japan, Italy. You pick up on the lingo and start to have your own little dialogue. And pretty soon you can revert back to something that you said maybe a month ago, just by using a punch line or a little joke that you’ve got going. And believe me, we’ve shared some good jokes on trips to other countries. To an outsider, a key word or line might mean little or nothing. But to us they contain a whole adventure.

For instance, I could say El burro es grande and Bob might double up laughing. Why? Well, it dates back to our trip to Mexico. I enjoyed the Mexican people very much – beautiful, beautiful people. And they have a great sense of humor, which of course is terribly important to me. And that’s where El burro es grande comes in.

I studied Spanish in high school and came out of the class with just one sentence – the one quoted above which means, “The burro is big.”

So while we were on location in Mexico, I would sit down on the grass with the Mexican crew – about 20 guys who took care of the lights and stuff – and I’d say, El burro es grande. And they would give me other lines: El burro es muy (very) grande. Si! (Yes!) And so on.

Well, finally it was time for Bob and me to return to California, and the majority of the crew came to see us off at the airport. And most of the son-of-the-guns had tears in their eyes. Then suddenly one of them says: “One, two, three …” and they all chimed out in unison: “El burro es good-bye!” So neither Bob nor I will ever forget that sentence. It turned out you could say quite a lot with it after all.

Then there was something that happened to Bob and me in Hong Kong while we were filming the 1st show in the series. Now, when I get to a foreign land I like to eat the food of the country. I don’t care how sick it makes me feel. Well, we were sitting in this restaurant. (A Chinese restaurant, of course!) Both of us had just learned how to work out with chopsticks, and were starting to learn a little about Chinese food, I mean real Chinese food. So we sat down and looked at the menu and said, “What is this?” and so forth and so on, and “Let’s have some of this. Have you ever tried this? No, man, let’s try some. Let us venture forth and get some of these wonderful things that they have on the menu here. We don’t care what it is. Give us some of this and some of that, with flangs and floosh and zoobie … and oh, yes, we must have some duck. Give us some duck. This barbecued duck here.”

Then there was something that happened to Bob and me in Hong Kong while we were filming the 1st show in the series. Now, when I get to a foreign land I like to eat the food of the country. I don’t care how sick it makes me feel. Well, we were sitting in this restaurant. (A Chinese restaurant, of course!) Both of us had just learned how to work out with chopsticks, and were starting to learn a little about Chinese food, I mean real Chinese food. So we sat down and looked at the menu and said, “What is this?” and so forth and so on, and “Let’s have some of this. Have you ever tried this? No, man, let’s try some. Let us venture forth and get some of these wonderful things that they have on the menu here. We don’t care what it is. Give us some of this and some of that, with flangs and floosh and zoobie … and oh, yes, we must have some duck. Give us some duck. This barbecued duck here.”

“It’s $36,” the waiter said, (That was Hong Kong dollars, but it still added up to $9 in American money.)

“Oh, so what!” we said, “We don’t care – $36 – man, give us the duck.”

So the guy’s bringing the food to us, and it’s all great – just great. Even the bean curds, which I’d never had before. Pretty soon we’re acting like high school kids – you know like fooling around with a chocolate sundae or something like that. And every time we’d taste something new, if it’s kind of weird, you look at your partner and your partner looks at you, and you break up laughing.

So we’re munching and crunching, till we’d finished a good part of the meal. (As a matter of fact all of it.) And I said to Bob, “Did we get everything – except the duck?” Bob said, “Yeah – we forgot the duck.” But we were both so full we couldn’t have cared less.

Then suddenly this guy comes up the stairs and over to our table – and he’s got a whole duck. What Bob had ordered was a whole barbecued duck! I was so startled I thought it was a joke, but it wasn’t. Now, we’re full of food – it’s up to the Adam’s apple, man. Well, we don’t want to make the guy feel bad, so we said, “Oh, this is wonderful …” Here are two guys so full of food, and now we’ve got to eat a whole duck. We’ve got to force it down.

The guy brought out the plum dressing and everything for it, and it was really delicious. I ate about two slices and Bob ate about two slices, and then I told the waiter, “Okay – put it in a bowser bag and we’ll take it home!”

And that’s what we did. We took it back to the hotel and gave it to one of the kids who worked in the lobby – they make like a penny a day. I’m sure that when he went home with a whole 36-Hong-Kong-dollars barbecued duck they all flipped.

Memories like that tie Bob and me together in a genuine friendship. It’s as genuine a friendship as any can be. There’s no pretending about anything. Although we have different tastes, we always respect that. He never demands anything of me – if I don’t want to do it, I don’t have to do it. There’s no argument, no walking off or anything like that. We don’t even have to pressure each other into saying, “Now, listen, man, if you don’t want to do it, you don’t have to do it.” That’s simply understood.

And if I ever take Bob some place that I think is special, and it fails, we both laugh – and vice versa. I went to the ballet with him one night. Went right to sleep. And we laughed and I thanked him. I said, “Listen, I probably would have stayed up til 12:30 – if I hadn’t gone to the ballet!”

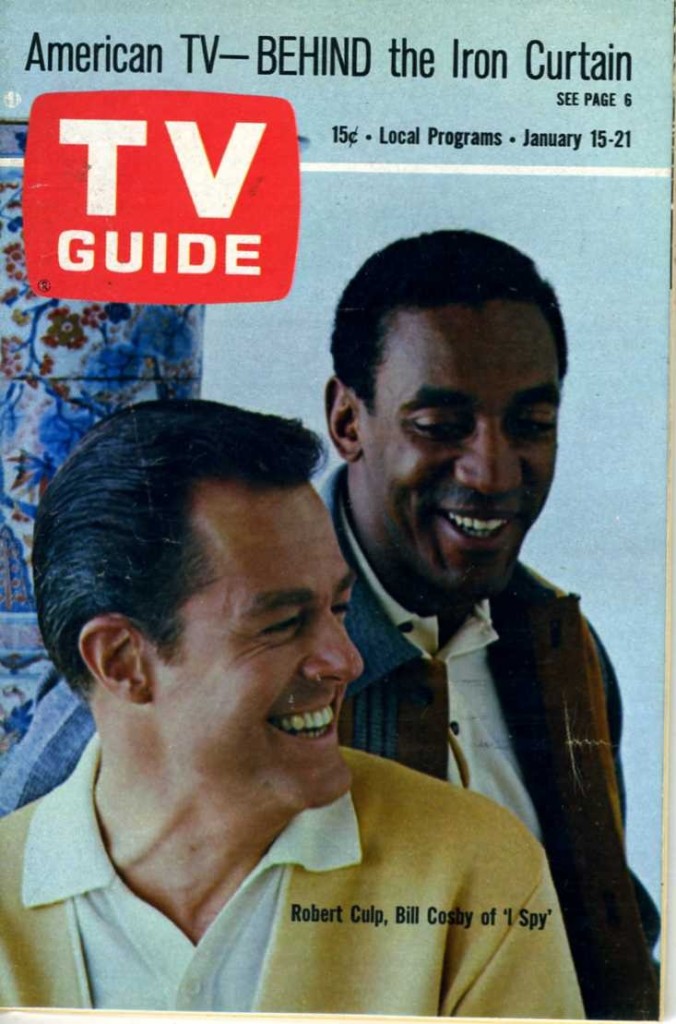

From TV Guide, January 15, 1966

Robert Culp’s character is revealed by his behavior on ‘I Spy’ and off.

BY DICK HOBSON

“Some of these white cats they say, ‘Hey, man, dig this, dig that, dig the other thing.’ When they talk like that they think they’re saying: ‘See? I’m with you. I’m sympathetic to the Negro cause.’ But I just say, ‘Man, you talk that way at home?’ I’d rather have a cat that shuts up and does it than a cat with the words. That’s what I like about Bob Culp. He’s a cat that does it. I got confidence in the man.”

The speaker is Negro comedian Godfrey Cambridge, all got up in white flannels and navy-blue double –breasted yachting jacket, as he paces the deck of a luxurious yacht on Stage 6 at Desilu-Cahuenga Studio in Hollywood. He awaits the nod of Robert Culp, who is directing his first I Spy episode, “Court of the Lion.”

“A Negro’s always got to be the Good Guy on TV these times,” Cambridge says. “I am tired of being loved. Now this king of the Zulus is the first villain I’ve been allowed to play on TV. I’m doing a black Goldfinger. Bob Culp had the guts to put me in this part. So many other people in this town would say, ‘Let’s not have an argument, let’s make the Zulu an Indian.’ But Culp says, ‘Let’s do it right.’ That’s what I like about Culp.”

Sagebrush Victorian would describe the style of Robert Culp’s dressing room: leather upholstery, bar with a foot rail, roll-top desk—a hark back to his days as Texas Ranger Hoby Gilman on Trackdown. Prominently hung in an oval gilt frame is a photo of Sammy Davis Jr. gripping Culp in a vigorous bear hug. The door is flung open and the minor whirlwind that is Bob Culp whips across the room, deflating into a chair, sandals flying. “First question,” he says, in the manger of a director saying, “Action.” The man is lean, athletic, brown of hair, hazel of eye, and looks rather professorial behind his horn-rim glasses.

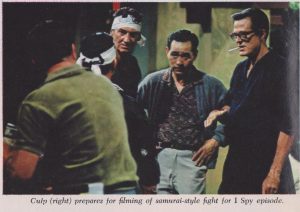

It’s true, he had to shell out $2000 to get into the Directors Guild in order to direct this episode, for which his director’s pay is $3500. He concedes he laid out $2500 for an artist to story-board the entire script. “Rarely can a man successfully act and direct at the same time. One has to suffer and it will always be the acting.” That conviction is what motivated Culp to hire acting coach Jeff Corey to stand by and observe his performance.

It’s true, he had to shell out $2000 to get into the Directors Guild in order to direct this episode, for which his director’s pay is $3500. He concedes he laid out $2500 for an artist to story-board the entire script. “Rarely can a man successfully act and direct at the same time. One has to suffer and it will always be the acting.” That conviction is what motivated Culp to hire acting coach Jeff Corey to stand by and observe his performance.

“At first I found only nitwits in this business,” Culp is saying. “I became childishly hostile. I got the image ‘troublesome.’ But I got wiser. I set about to rectify my ways.”

One of those to whom he was “childishly hostile” was Vincent Fennelly, producer of Trackdown, the series Culp starred in back in 1957. Fennelly claimed Culp walked more like a Method actor than a Texas Ranger, and for a year they didn’t speak to each other. “Yeah, he thought I walked funny,” Culp says, “I invented my own kind of slouch-stroll. Fennelly’s an accountant. He wanted the same old Western hero. But he was right; I was wrong. In Omaha they couldn’t care a rat’s nose.”

*****

A thick blue pall clouds the dressing of Bill Cosby, first Negro to co-star in a network dramatic series. Cosby is stretched over an easy chair, puffing on a 9-inch cigar, sprawled under a framed photo of the co-stars dressed in tennis garb.

“I could be just a nothing. I could be crumpled and crushed if Bobby had turned out to be the kind of guy who wants everything for himself,” Cosby says. “But we made contact. We tuned each other in. Now Bobby knows me better than anybody. We’re closer than brothers.” Godfrey Cambridge sidles into the room and pours himself some coffee, picking up the drift of the conversation. Cosby continues: “We don’t have any race jokes in the scripts. Even in real life, race jokes would be embarrassing to Bobby and embarrassing to me.”

But what about Sammy Davis Jr. and the Clan? They’re integrated and they make ethnic-type jokes. “The old-timers like Sinatra do it. But the Clan has guilts and complexes. They’ve always got to talk about race. It’s very corny, unhip. We’re beyond that.

“You know how the Clan has to have a Leader and all that? No King of the Road with us. Bobby and I are equal. Another thing, we’re closer to the people. The Clan could play golf on Forest Lawn, they’ve got so much money.”

*****

Out in Woodland Hills in San Fernando Valley waits Culp’s wife, the former Nancy Wilner (or former Nancy Asch, actress-theatrically speaking), described by a close friend as “nutty, droll, and bright.” “I hate being called a ‘former’ somebody. Just say I’m the current Mrs. Culp. There was a previous Mrs. Culp, you know—Bob’s college drama coach. She was 24; he was 19. I think she was another mother to him. Shall we tour the homestead?” It’s a big, old frame house with an oversize cupola, a decidedly eccentric house among all those new-moderns in suburbia.

“This is the playroom. This is Jason’s room. This is Joshua’s room. This is Joseph’s room. This is Rachel’s room.” All but one of the offspring are pre-schoolers. One room has a jungle tree-house in one corner and bunks suspended from the ceiling on chains. “Bob did it.” Another is fitted like a ship’s cabin with bunks, ladder, and real portholes. “Bob built it. This is our kitchen. Bob laid the floor.

“We first met at an off-Broadway theater. Off-stage he was very shy, insecure, ill-at-ease. But on-stage he could do the most fantastic things. We did the Greenwhich Village scene together, the Brando thing, the motorcycles, the whole bit.”

On a peg hangs a black cowboy hat. “Gary Cooper’s. Bob wore it in a Gunsmoke.” The oversize cupola on the third floor turns out to be Culp’s study. “We call it the Lion’s Den.” Up here Culp has a 360-degree view of his two-acre wooded domain. Here is his typewriter.

“Bob’s first script was a Trackdown. He thought all the stories were adolescent drivel. So he just wanted to do one that would be his own way. But Trackdown was an unhappy period for us. It was agony for Bob to go to the studio each day. He was hanging on for dear life. I didn’t know from one day to the next whether he would come home or not. Sometimes he didn’t.”

*****

After Trackdown, Culp loudly let it be known he wanted no more of series. “Bob had a reputation as being quite tumultuous,” agent Jimmy McHugh says of him. “He’s one of those actors who has a deeply rooted desire to say something in his work. But Hollywood is not that kind of town.” Culp says: “Jimmy helped me change. He set out to make a comedy image for me and he did a beautiful job.” In two years Culp made four feature pictures, including “Sunday in New York.”

Any discussion of I Spy invariably returns to the Culp-Cosby relationship. Mark Rydell, who has directed three I Spy episodes this season, says: “Bob could easily overpower Cos simply by exercising his talent. But Bob is always helping Cos and guiding him in a way that I find quite moving.”

“Half of my energy is spent trying to translate their private communications,” says Paul Wendkos, director of eight of this year’s I Spys. “Culp and Cosby have put-ons on top of put-ons. They’re ‘hippies,’ to use one of Bob’s favorite words. They always take the off-beat way. But underneath their hip, existentialist veneer is the sense of irony just this side of bitterness- the irony of the artist in show business, the irony of racial inequality.”

“Bob is incensed by prejudice,” says Culp’s friend, director Sam Peckinpah. “He doesn’t recognize it; he doesn’t understand it. Yet he’s not trying to carry any particular banner.” Wendkos adds: “Bob’s attitude is, ‘I don’t have to crusade. I’m it.’”

According to I Spy co-producer Mort Fine: “There is a wide audience acceptance of the camaraderie between Culp and Cosby, the white man and the Negro. People want to do the right thing, white to Negro. I think it’s vicarious. They want to watch it in action.”

“Yeah,” says Godfrey Cambridge sardonically, “watching I Spy on the tube provides a relationship with a Negro with no risk.”

As for Bob Culp, he says only, “If Cos and I have any kind of mission on this show, it’s something we’ve never had to discuss.”